Seoul City Sue: A Prologue

Those of you who 1) know me in real life and b) read this blog know that one of the plays that I’ve been working on recently is called Seoul City Sue. Unfortunately, there’s not a whole lot I can say about the plot of the show, mostly because it’s still in active development but also because it’s very easy to spoil.

So in lieu of that, I thought it might be worth using this blog as a means to talk a bit about the research that’s going into this play. I’ve been working on this play on and off for a little over a year now, so there’s a lot of information I’ve gathered that is worth knowing about. Perhaps we could call this a prologue to the play. Or a companion piece. Or a dramaturgical note. One of those.

Propaganda

In times of war, it is not uncommon for a particular country to create propaganda radio broadcasts aimed at the opposing country. The most famous example of this is Tokyo Rose, the name given to various voices broadcasting English-language propaganda from Japan during World War 2. Other examples include Lord Haw-Haw (yes that’s what they called him) from Nazi Germany and Hanoi Hannah from North Vietnam.

The same occurred during the Korean War in the 1950s: the DPRK regularly broadcast English-language propaganda over the course of the war, aimed at the American soldiers. The most famous voice from these broadcasts was one that broadcast from around the beginning of the war in June/July to the Inchon landings in September. She went by various names: “Rice Bowl Maggie,” “Rice Ball Maggie,” “Rice Ball Kate” (these American soldiers weren’t very imaginative). But the name that stuck was “Seoul City Sue.”

Seoul City Sue was considerably less popular among American soldiers compared to her Japanese-equivalent Tokyo Rose, because her broadcasts apparently sucked. Generally, broadcasts consisted of her reading out the names of captured POWs in a dull monotone and issuing empty threats to new units. She was also known to taunt African-American soldiers about their limited civil rights back home. An actual quote from an UPI correspondent during the war:

She talks in a monotone. Her voice is icy. She exudes the passion of a well boiled vegetable. What in the name of Lenin she thin[k]s she is going to accomplish and who in tarnation she expects to impress with her type of spiel beats the living daylights out of me….

She can't kid the GI. He's been kidded by experts in all sorts of propaganda since childhood. Also he's accustomed to getting some entertainment when he turns on the radio. Seoul City Sue gives him amateur kidding and no entertainment at all.

As you can hear in the video above, she also played music, although she never played anything popular which made the soldiers even less-inclined to enjoy her show.

So, who was Seoul City Sue? Was she a Korean woman who just happened to speak fluent English? Well, it was possible… but there was something about the speaker’s grasp of the English language and regional accent that suggested her origins lay stateside…

Anna Wallis Suh

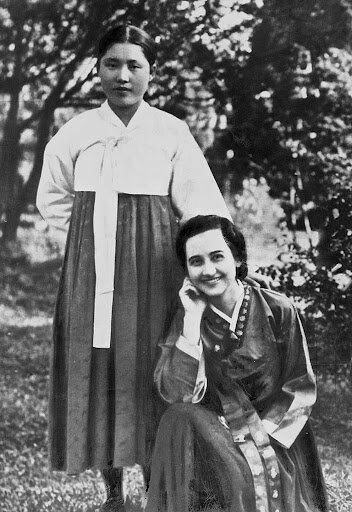

Meet Anna Wallis Suh, an American missionary from Arkansas. Born Anna Wallis in 1900 (I can’t find an exact birthday), she was part of the American Southern Methodist Episcopal Mission in Korea beginning in 1930. Although the original goal of these missions were to spread Christianity, the Japanese banned proselytizing in the early 1930s as part of their general imperialism push, so Anna Wallis’s duties probably involved general education. She spent the better part of the decade in Seoul and probably became quite familiar with the locale.

In 1938, Japan officially banned missionaries from Korea and she relocated to the Shanghai American School, where she met and eventually married fellow staff member Kyu Chul Suh (서규철). What she did not know at the time was that because Suh was a national of the Empire of Japan when they married, she was no longer an American citizen.

An interesting counterpoint: Japan was a multiethnic empire at the time, which meant in Japan’s eyes Anna was still an American. I wonder what she must have thought of that.

After World War 2 ended she and Kyu Chul moved back to Seoul, where she took a job at the US Diplomatic Mission School. She taught there until 1949, when she was fired because her husband was suspected of “left wing political activities.” Essentially, he was an early supporter of communism, and it is known she had taken an interest in the same political ideas since they married.

The question, of course, is this: were the Suhs supporters of Kim Il-sung, the then-supreme leader of North Korea? That’s a bit unclear, but it is interesting that despite their left-wing interests they remained in the US-backed right-wing South Korea.

Whatever the reason, the Suhs were still living in Seoul on June 25, 1950, when a pretty major conflict changed their lives forever.

육이오 (The June 25th Invasion)

As we know, the North Koreans crossed the 38th Parallel on June 25, 1950, which started the conflict we know as the Korean War. The invasion took the South Korean population by surprise despite days of reports that the North Koreans were preparing for a major skirmish. These reports never made it to the South’s population because of the South Korean propaganda machine, which didn’t acknowledge a North Korean invasion until they were practically in Seoul already. The North Koreans quickly overtook much of the South in a matter of days, controlling a majority of the Korean peninsula.

Because there had been no organized evacuation, sixty members of the Republic of Korea National Assembly were still in Seoul when the communists arrived. Around the end of July, 48 of them held a meeting where they – willingly or not – swore allegiance to North Korea. Among the people at the meeting was none other than one Anna Wallis Suh, who was about to become a major figure in North Korean propaganda.

The program that became known as the “Seoul City Sue” radio show began on or around July 18. Broadcast live from KBS’s HLKA Studios, the daily programs ran from 9:30am to 10:15pm local time. The station producer was Dr. Lee Soo, who was an English instructor at Seoul National University. For the duration of the program’s run in Seoul, the Suhs lived at a temporary home a few blocks away.

It’s not entirely clear if the Suhs did this all by choice. By all accounts they were leftists, which in those days meant they were aligned with the idea of a communist Korea. Despite our current perspective on North Korea, during Kim il-Sung’s leadership his supporters had little-to-none of the cynicism that present-day North Korean citizens have to his descendants: they truly believed in the superiority of a communist North Korea. It didn’t matter if his actions were to the contrary: the government had too much of a hold on how information as spread for the average citizen to hear the truth.

However, statements from Anna’s relatives, who heard the broadcasts, insisted that she was being forced to do so. They pointed to her dull delivery as evidence she was coerced into doing the broadcast, and that she clearly had no enthusiasm for what she was saying. It is worth noting that Anna had a different cultural perspective from the average Korean citizen. Even if she was a supporter of Kim il-Sung early on, it doesn’t take a stretch of the imagination to believe her allegiances changed living under his policies (more on that later). But that’s just me.

After the Inchon landings, the Suhs were evacuated up north, where they subsequently joined the staff of Radio Pyongyang. Anna is known to have continued her English-language broadcasts from that station. It is possible, though I haven’t been able to confirm this, that she is the same voice of a figure known as “Pyongyang Sally,” another alleged propaganda voice used by the North Koreans.

The Fate of Seoul City Sue

This is where information about Anna gets a little hazy, because as we know it’s very difficult to get much information out of North Korea beyond what the government allows. What is definitely known is that in February 1951 Anna was reassigned to POW Camp 12 near Pyongyang, where she was instructed to indoctrinate the UN soldiers imprisoned there, and to teach them to indoctrinate each other. From what I can tell, she continued broadcasting until the end of the Korean War. And that’s the last anyone heard of her for nearly half a century until 2004.

Enter Charles Robert Jenkins, an American soldier who had defected to North Korea in the early 1960s to escape the incoming Vietnam War. Jenkins was able to leave North Korea in 2004 due to some complicated diplomatic activities that I won’t bore you with, and later published a book about his experiences. This book included the first new information about Seoul City Sue in 50 years… and it wasn’t exactly good news.

Disclaimer: Jenkins’ testimony hasn’t been independently verified – mostly because how can you verify something in a country where truth is a fickle thing? – and there’s always the possibility he misremembers some things from his time in North Korea. He was, after all, there for half a century. Use your own discretion in deciding how much is true.

Jenkins heard about Anna (who he knew as Suhr-Anna) pretty quickly, due to there being very few Americans in North Korea at the time. The popular narrative going around was that she was married to a North Korean sympathizer who was executed by the South during the invasion for broadcasting about the communists, and that she defected in honor of her dead husband.

Okay, that’s… that’s definitely not what happened, but that’s how the North Korean propaganda machine works. It twists stories in the name of showing how great the DPRK is. Unfortunately, this does not bode well for one Kyu Chul Suh: the narrative would not work unless he was already dead, and all evidence shows he was alive when the Suhs moved to Pyongyang. So between then and when Jenkins arrived, Kyu Chul bit the bullet. Unfortunately, because of these drastically different narratives, it’s impossible to tell what exactly happened to him.

She is known to have participated in a propaganda pamphlet with another American defector in 1962, and that she was put in charge of the English-language division of the Korean Central News Agency. It was in Pyongyang in 1965 that Jenkins met Anna Wallis Suh for the first and only time.

…I recognized her from [a propaganda pamphlet], so I walked up to her and said, "Hello, Suhr Anna-senseng" (senseng is the Korean word for "teacher"). It was winter, and she was wearing a black leather overcoat, very put-together. She looked surprised and turned, looked at me, and said, "Oh, you must be the American who just came over." I said, "Uh-huh," but she was spooked. The second we met, she wanted to get the hell out of there. She excused herself, saying she really needed to be going, and was gone.

(from The Reluctant Communist by Charles Robert Jenkins)

In 1973, Jenkins and another American defector, James Joseph Dresnok, were working at the Pyongyang University of Foreign Studies when another instructor let them know he was going to the Korean Central News Agency. Dresnok called out off-hand “Say hi to Suhr Anna for us!”

The instructor looked horrified. “You want me to say hello to that dead, goddamn spy?!”

It was then that Dresnok and Jenkins learned that in 1969, Anna Wallis Suh was accused of being a double agent for the South and immediately executed.

This double agent thing is what trips me up. Was she a double agent from the start – was she assigned by the Korean National Assembly to spy on the North because of her bilingual skills? Did she defect to the South after seeing Kim il-Sung’s policies in action? Or did she do something to annoy the North Koreans that led to them executing her, and the propaganda machine made up the story that she was a double agent? What happened to her husband? Was she actually killed in 1969?

Whatever happened, Jenkins never saw her again, and no defectors have ever shared stories about seeing the only white lady in North Korea.

Legacy

Although the U.S. certainly investigated Anna Wallis Suh during the war, she was not a priority for retrieval or rescue due to no longer being an American citizen. Besides, her propaganda broadcasts were never perceived as a threat the way Tokyo Rose’s were, mostly because they weren’t as widely listened by the American soldiers. I recently asked my grandfather, who was a translator for the U.S. forces in the Korean War, if he could recall anything about an American woman doing English-language propaganda on the radio. He vaguely remembered hearing about Seoul City Sue, but not in a lasting way. In fact, outside of the soldiers, most Americans didn’t even know the name “Seoul City Sue” until she was referenced on several episodes of the TV show M * A * S * H, which was set during the Korean War and featured recreations of her broadcasts. Still, in the annals of history, Seoul City Sue seems to be just a little bit of trivia from the Korean War.

Still, there’s something striking about this image of an American woman trapped in the monolith we know as North Korea, whose ultimate fate has this big question mark looming over it. There’s something incredibly lonely about that, perpetually living as an outsider in a country that will probably never quite trust you no matter what you do. Just what information is hiding beyond the DMZ, in a country where verifiable information is hard to come by? Seoul City Sue doesn’t have much of a legacy in the U.S., but does she have one in North Korea?

Someone ought to write a play about that.